Focus, But Where?

‘Focus, But Where?’ is a web-based hidden object game that playfully explores the intersection of climate change activism and our complex digital landscape.

Its initial narrative and concept design were created during Kexin Liu’s Research Residency at Watershed’s Pervasive Media Studio (01/02/2023-13/04/2023) and were further developed with the generous support of Grounding Technologies (01/08/2023- 01/12/2023), funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and Department for Media, Culture and Sport. Currently, we have a completed script, 35% of the illustrations, and a basic open-sourced game development framework all available at Github.

Kexin Liu (project director) in collaboration with Kai Charles (researcher & writer), Inigo Hartas (illustrator), Xingzhi Zheng (game designer & programmer), Jake Wild (sound designer), and Jiashun Wu (programmer). Bristol, 2024.

The Inspiration – It All Started With A Can of Soup

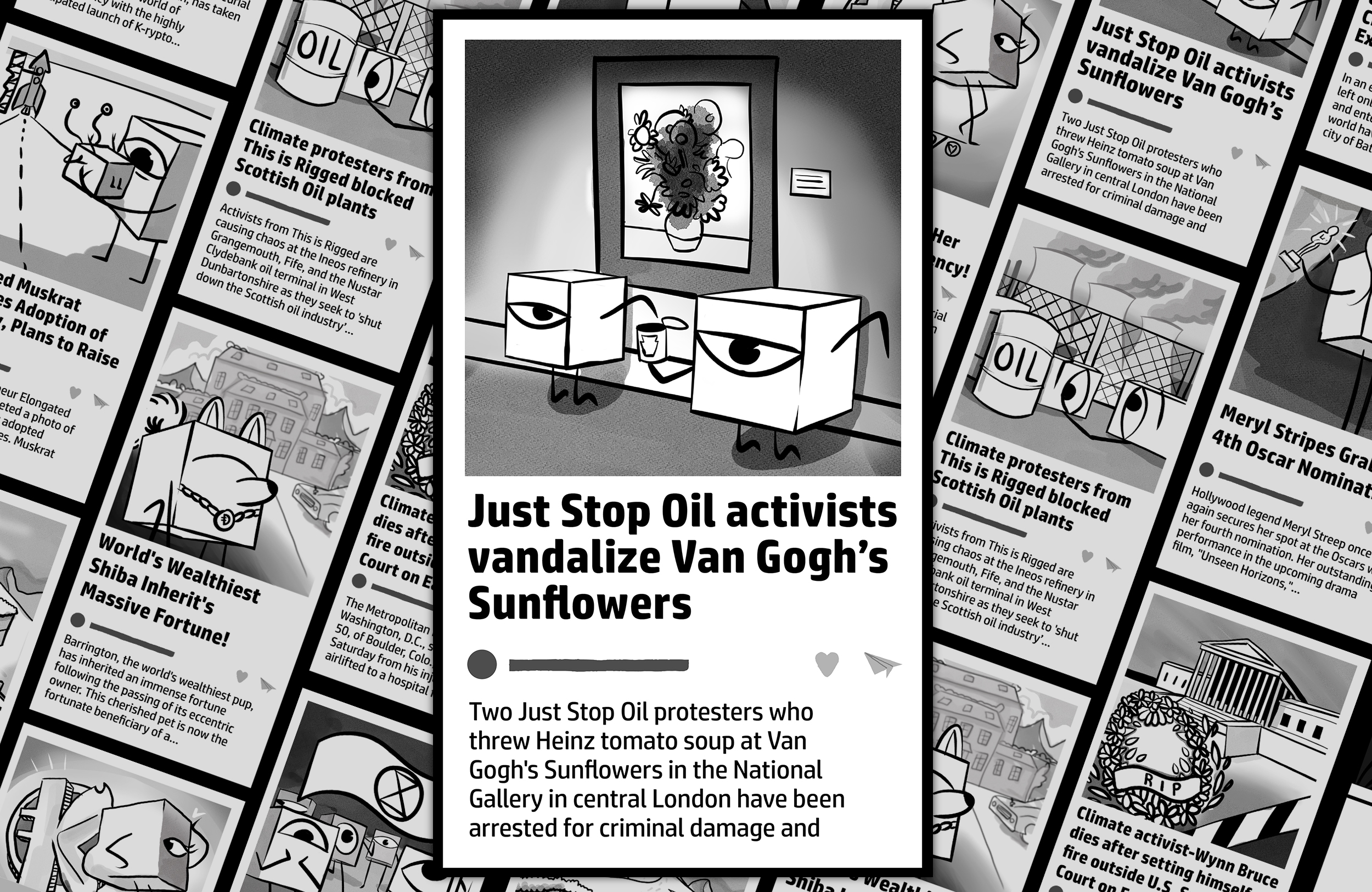

The climate protest happened at the National Gallery in October 2022 was one of the biggest inspirations for creating ‘Focus, But Where?’ Remember when two JSO members made headlines by splashing tomato soup over Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, inspiring a trend of “attacks” on valuable artworks by different climate groups, sparking a whirlwind of online drama?

There were heated debates around the protestors’ controversial tactics … While critics argued that disrupting public life is unacceptable and counterproductive, supporters claimed that pissing people off is exactly the point – radical movements like this are not meant to make sense, but to keep people enraged and engaged, putting climate action under the spotlight of public discussion … Countless sensational media reports also added to the confusion … For example, many news articles portrayed the incident as “vandalization,” leading readers to believe the painting was damaged, when in fact the painting was protected by safety glass, a fact the activists were well aware of… Not to mention all the conspiracy theories suggesting that the campaign was backed by oil companies all along …

But instead of concentrating on the protesters’ eye-catching tactics, or blaming the media for prioritizing clicks and profits from inciting outrage, and the millions of onlookers (including us) who are constantly scrolling their phones for distraction. We want to gain some clarity on the negative cycle of digital consumption that we all contribute to, and ask: Are there any practical ways for us creatives to improve our mode of climate communication?

But where should we start? We can’t tell all the climate activists to stop splashing liquids on famous artworks since it is extremely difficult to measure the long-term effects of radical protests, especially in regard to cli- mate change, where scientific research is consistently influenced by political agendas and corporate interests. We also can’t force the media to uphold the integrity of journalism when the algorithm developed by tech companies doesn’t tend to reward the most accurate and nuanced opinions.

What we could do is address the social and psychological aspects of climate action by promoting digital literacy and a deeper empathy for all parties involved through interactive storytelling. After all, there’s a deep link between our physical and virtual world, and it is impossible for us to push radical changes in our natural environment without transforming the digital landscape we inhabit.

Gameplay Mechanics

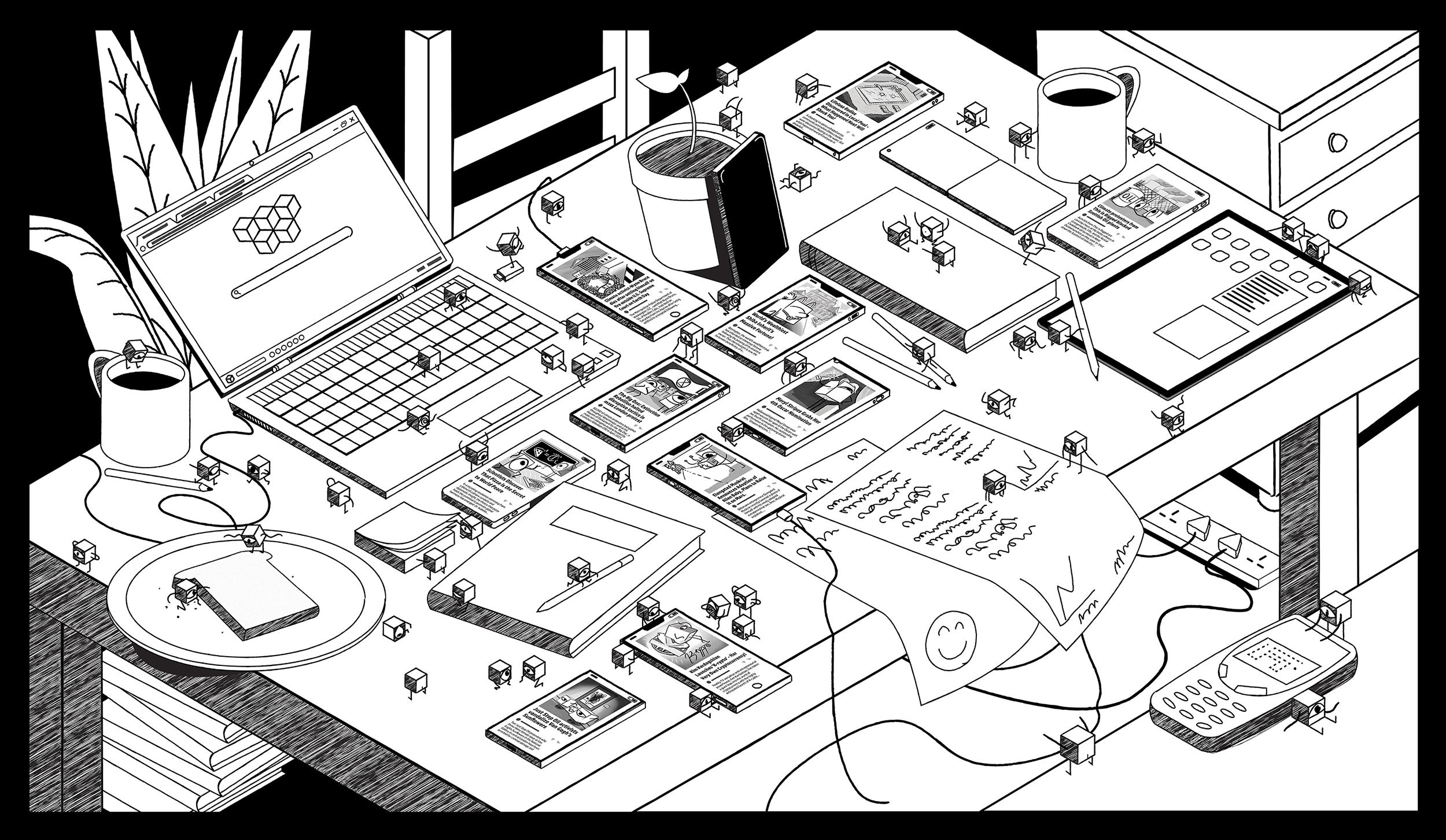

In terms of gameplay mechanics, the game follows the classic hidden object genre. Players explore var- ious scenes, uncover hidden objects relevant to climate change, and collect them in their inventory. This inventory then grants access to educational content and references on specific climate-related issues.

This project leverages the game engine phaser.io and Tensorflow face landmark detection framework. We offer two interaction modes: standard cursor-based navigation and a hands-free option that enables players to use their gaze to navigate the game and trigger interactive animations through eye movements like blinking and staring. This innovative gameplay experience underscores a key element of our narratives—the dynamics of attention, distraction, focus, and changes in perspective surrounding environmental issues.

Game Narratives

Chapter 1: Lost in The Flood

In this opening chapter, we highlight how important issues like climate change are often drowned out by attention-grabbing but inconsequential tabloid entertainment news. In this instance we ask our player to spot the three climate-related articles amid this flood of digital content with the visual clues we give out.

Chapter 2: The Soup and Van Gogh

The second chapter focuses on a famous climate protest: the Van Gogh soup protest. By analysing the ini- tial public response, examining the protest’s portrayal in the media, and drawing from historical instances of radical protests, we aim to uncover reasoning behind the protest, it’s impact on the national discourse, and the attention it garnered across the media landscape. In one section we explore the omission by the media of the fact that the painting was protected by safety glass, a fact the activists were aware of. This omission drove much of the rage directed at activists, at the same time without it the story would have been unlikely to gather the attention it received.

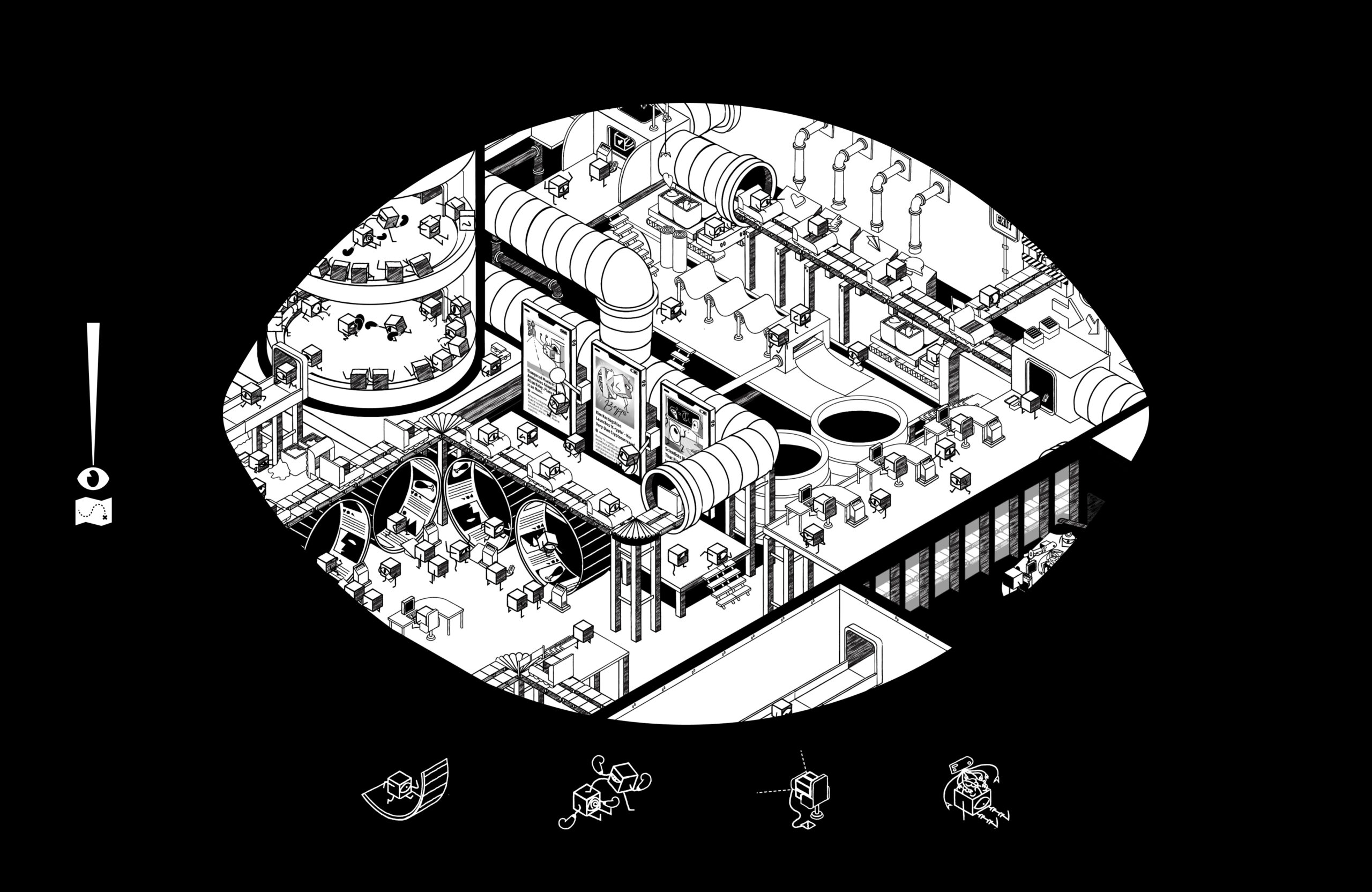

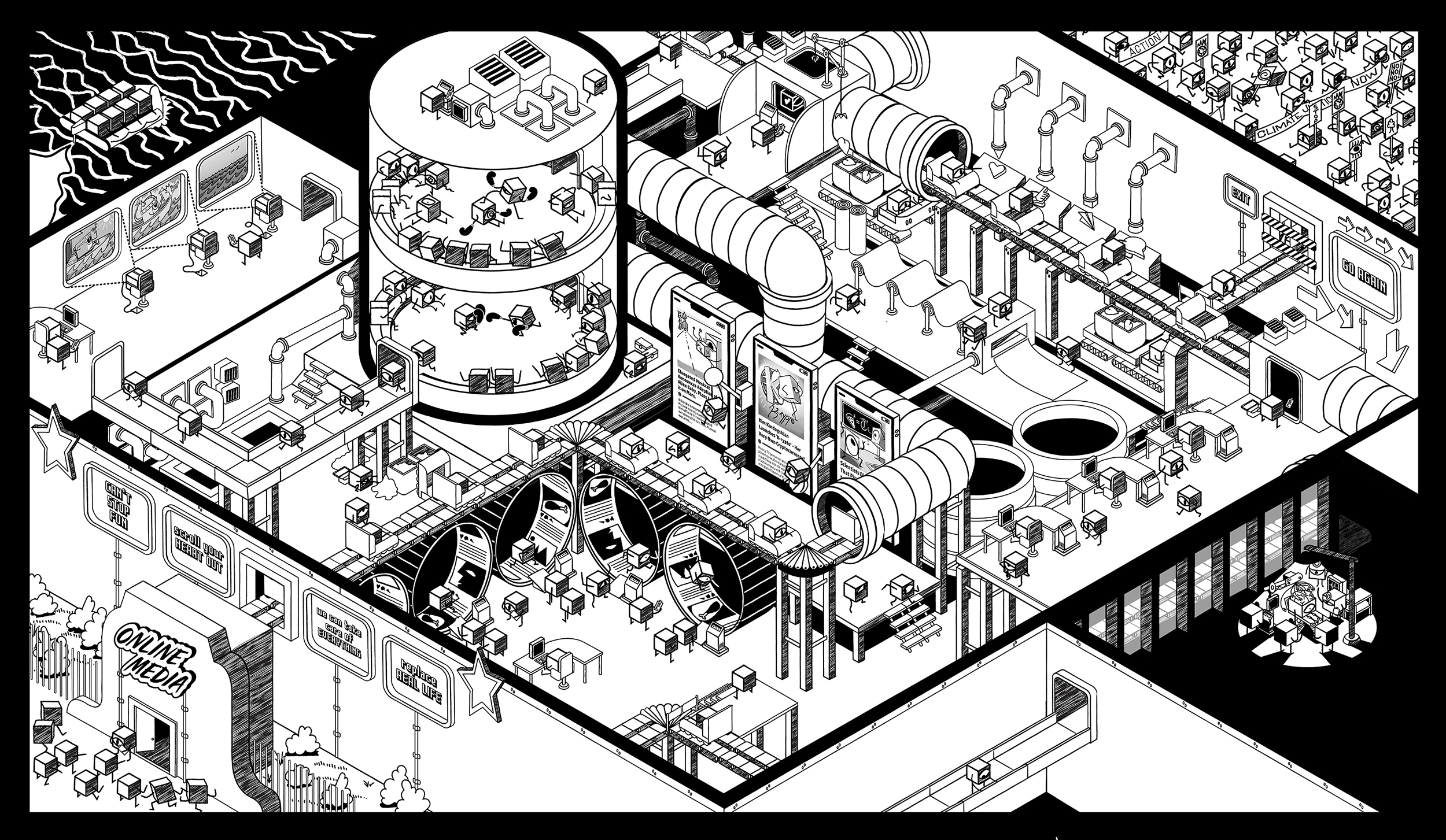

Chapter 3: Addict Factory

Chapter two naturally leads to the question of why? Why is our digital landscape such that only an act such as the Van Gogh protest breaks through for more than a moment? This chapter seeks to answer that question. We illustrate how our online world contributes to echo chambers, extremism, and addiction, touching on manipulative UX/UI designs crafted by tech companies, the attention economy that dominates discourse and the commodification of human weaknesses, turning us into products rather than customers.

Chapter 4: The Spiders in The Attic

The Spiders in the attic focusses on influence of lobbying bodies and the ultra wealthy on the media we consume. In particular it discusses the demonisation of activists and the normalisation of violence, both from the public and the police, against them. It presents the interconnection of lobbying bodies, politicians, and press through the imagery of spiders languishing in a dusted attic, each spider revealing another layer of influence.

Chapter 5: Zooming Out of Our Paper House

In the final chapter we zoom out from the media landscape the game has navigated throughout it’s run to witness the future that looms if we fail to act. Flood water rises to consume a city, paper houses dissolving into a wall of water. Fire races across the world. The game leads players through a landscape of over- whelmed health services, failing crops, and compounding catastrophes underscoring the horror hidden amongst the discourse.

Chapter 6: A Note of Hope

In the final section we will give out our reasoning on creating this game, and useful resources to encourage the player to take some form of action to push back against the escalating climate catastrophe calling for hope and action rather than division and doom.