Treasure Hunting for Queer Chinese Objects in UK Museums

Why I Started This Search

In recent years, UK museums have made significant efforts to improve the representation of LGBTQ+ communities within their collections, largely in response to the growing demands from activists, researchers, and queer community groups frustrated by the longstanding marginalisation of queer people in cultural institution.

As someone fascinated by LGBTQ+ subculture, I’ve started paying close attention to queer objects featured in these hidden histories trails whenever I get to visit a museum in a new city.

Unsurprisingly, most of the objects I encountered were European, i used to think this is probably due to the focus on regional history and the scope of the collections. But I started noticing something strange, even in East Asian collections, where Chinese artefacts often make up a significant portion, I couldn’t find any Chinese objects highlighted as queer with a rainbow symbol on top of their label. Where were all the queer Chinese items?

The feeling really sank in when I bought A Little Gay History, by Dr. Richard Parkinson, a popular little book showcasing a selection of queer objects around the world from the British Museum’s collection. I eagerly flipped to the page where there’s a world map dotted with the locations of these objects, hoping to find some connection to China. But the absence was stark— there’s not one red dot in China.

The book is self is only 132 pages long and it said at the very beginning that this is providing a glimpse into a brief history. But still, I thought, surely one or two Chinese objects would make the cut, given the enormous trove of over 23,000 artefacts from China in the British Museum.

Intrigued and frustrated, I took my search online. That’s when I stumbled upon an article claiming that in 2013, the British Museum had banned Chinese artefacts from appearing in Dr. Parkinson’s book. Out of the fear that including these objects would jeopardise a negotiations for a Ming Dynasty exhibition with China at that time. The implication was that China’s censorship on LGBTQ+ issues had pressured the museum into self-censorship.

Curious, I reached out to Dr. Parkinson himself to verify the story via email. According to Dr. Parkinson the press story was “not entirely accurate.” No Chinese objects had been chosen for the book because he was unfamiliar with the Chinese collection. While he had considered including something related to Emperor Ai of Han and the “passion of the cut sleeve,” his colleagues in the Chinese department were preoccupied with negotiating the loan and couldn’t help with selections at the time.

So, it wasn’t deliberate censorship, but more of a case of neglect due to limited resources.

Still, the lack of representation gnawed at me. Could it really be that there were no recognised queer Chinese objects in UK collections?

The Treasure Hunt begins

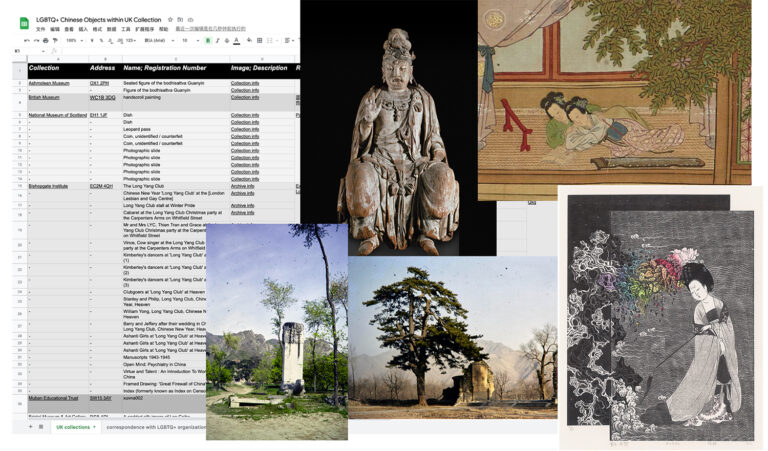

In early 2023, I started reaching out to UK institutions with moderate to large Chinese collections, as well as LGBTQ+ organisations and researchers involved in designing queer history trails, in an attempt to answer this question.

The answer, it turns out, is more nuanced. In short, yes—there is indeed one Chinese “queer object” featured in a queer history trail at the Ashmolean Museum. A few more objects have been identified as having queer connections across various collections, as noted by curators and archives during my research. However, none of these objects have been officially highlighted or labelled as LGBTQ+, either because they aren’t considered representative enough or because they remain understudied.

That said, most of these recognised objects, in my opinion, have little to do with China’s LGBTQ+ culture. For instance, depictions of androgynous deities like Guanyin and Lan Caihe, which are commonly found in Chinese collections, are often used in museums to draw parallels with trans identities. However, in the context of Chinese culture, the androgyny of these deities is part of their nature as transcendent beings free from earthly gender distinctions, symbolising harmony and balance. This has no connection to sexual and gender minorities or their experiences whatsoever.

Meanwhile, historical queer figures and narratives clearly related to sexual minorities in China, such as duishi and nanfeng, have hardly been studied at all.

We all draw on historical and cultural knowledge to construct a sense of identity, but in doing so, we risk projecting Western ideas of sexuality and gender identity onto non-Western perspectives. The museum curators I spoke with are aware of this issue, which is why they have not officially labelled these objects as LGBTQ+ in the first place.

So why aren’t more objects being discovered?

I suspect it’s a combination of factors. LGBTQ+ love is one of many intimate human desires that museums have traditionally disregarded. In addition, China’s censorship policies over the past few decades have heavily impacted LGBTQ+ art, literature, and academic research. Pre-modern Chinese items are already dense with allusion and symbolism, and the lack of reference material makes it difficult for curators to identify and acquire such objects. It demands a high degree of knowledge and cultural sensitivity.

Another challenge in increasing LGBTQ+ visibility in collections is the way objects are traditionally catalogued. To fit into a museum’s taxonomy, physical objects are often divorced from their previous owners and environments, stripping away the context of queer associations and narratives. This issue affects the preservation of both Chinese and Western queer heritage.

Many of the institutions I contacted admitted they had done little to no prior research on the subject. Despite the help of curators and researchers, I managed to identify around 40 queer Chinese items across UK collections. Even then, many of them felt repetitive, revealing the limited academic foundation guiding these efforts.

Resources and tips for curators that want to join the treasure hunt

Suggestions on acquiring objects related to LGBTQ+ communities in contemporary China:

1. Danmei(耽美) literature:

Danmei, namely “indulgence in beauty”, is a genre of fanciful literature on male-male romantic relationships created and consumed mostly by straight women and sexual minorities. This literature genre was first introduced to China in the 1990s through Japanese Boy’s Love manga and anime, over the past decades it has gradually integrated Chinese homoerotic culture and developed into a local genre with millions of dedicated fans.

You can find Danmei book and merchandise through platforms like Jinjiang(晋江) and Changpei(长佩). There might also be posters available for web shows adapted from popular Danmei novels such as Zhenhun, The Untamed, and Addicted.

It is important to note that this genre does not provide a realistic portrayal of homosexual relationships, and since LGBTQ+ content is strictly censored, especially depictions of physical intimacy, most of the “clean versions” of the publications and shows we see now have been criticized for queer baiting. Nevertheless, it provides insight into the Chinese LGBTQ+ subculture and illustrates the dilemma many LGBT content creators face.

2. Artworks by queer Chinese artists:

Most Chinese artists that produce LGBTQ+-themed work can be tracked through group exhibitions held outside of mainland China, You can find artists you are interested in and wish to acquire artwork from by browsing exhibition catalogs or online artist talks such as Secret love 2013, Spectrosynthesis 2017, and Shanghai Pride Art.

Wangzi’s hail comrade series and Xiyadie’s paper-cut pieces would, in my opinion, be the best examples in terms of artistic originality and cultural representation. (A fascinating aspect of Wang’s practice is that he often appropriates propaganda in a cheeky mischievous way, which perfectly echoes Chinese e’gao culture. There isn’t much information available on the artist and his artworks aren’t as prominent as they should be. The only interview I found of him is in Chinese.)

3. Film that reflects contemporary Chinese LGBTQ+ community:

East Palace, West Palace: the story is based on gay persecution at Beijing’s famous cruising ground

(The screenplay for this movie is written by the late Wang Xiaobo. He and his wife Li Yinhe are considered to be the most influential scholars in studying Chinese LGBTQ+ subculture, so they are also worth looking into)

Farewell My Concubine: touches upon the blurring of gender identity in Peking Opera and persecution during the cultural revolution.

The Wedding Banquet: touches upon Xinghun(形婚) and cultural differences regarding same-sex relationships.

4. Queer celebrity/icon:

Jin Xing, Ren Hang, Leslie Cheung, Kevin Tsai (I have only included some of the most famous and indisputable ones)

5. Social phenomenon: Tongqi(同妻) and Xinghun(形婚)

Tongqi refers to straight women that are tricked into marrying closeted gay men. And Xinghun is a sham marriage between a gay man and a lesbian, this type of arrangement often aims to meet parental & social expectations without deceiving innocent people.

There are an estimated 16 million Tongqi living in China currently, and they often suffer from social stigmatization and domestic abuse. underground Tongqi chat groups and forums do exist, but I do not have any direct links to them or any idea about finding objects related to this community. Similarly, there are also chat rooms and sites dedicated to Xinghun matchmaking that people around me use. They are less discrete than the Tongqi ones but still, they mainly exist online, and there will always be problems when we try to rely on material culture to represent marginalized groups.